|

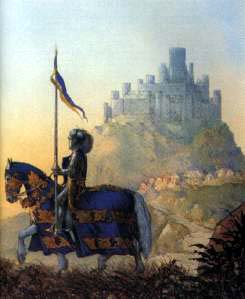

Ivanhoe, Robin Hood, Lancelot, and Joan of Arc -- the very names ring with chivalry. The question then is "What is Chivalry?" The word comes from chevalerie which derives  from cheval, French for horse. And the horse is what set the knight apart. Remember Richard III's cry in Shakespeare, "My kingdom for a horse." The Europeans bred the draft-type horse up in size and strength to carry the ever increasing weight of an armor-bearing knight. Stirrups, which had been brought from the east in about the eighth century, stabilized this armored, lance-bearing warrior astride his gigantic steed. Before stirrups, you clung on as best you could. The shock attack of medieval knights was a weapon of great impact, indeed a military revolution on horseback. from cheval, French for horse. And the horse is what set the knight apart. Remember Richard III's cry in Shakespeare, "My kingdom for a horse." The Europeans bred the draft-type horse up in size and strength to carry the ever increasing weight of an armor-bearing knight. Stirrups, which had been brought from the east in about the eighth century, stabilized this armored, lance-bearing warrior astride his gigantic steed. Before stirrups, you clung on as best you could. The shock attack of medieval knights was a weapon of great impact, indeed a military revolution on horseback.

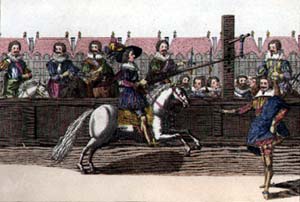

The words "tournament" and "joust" are often used interchangeably. Strictly speaking "joust" describes single combat between two horsemen. "Tournament" refers to mounted combat between parties of knights, but also is used to refer to the whole proceeding. The first written tournament guidelines are usually credited to a Frenchman named Geoffroi de Purelli in 1066. Unfortunately, he was killed at the very tournament for which he made the rules.

War, as a regular occupation for a gentleman, had many disadvantages. Although it was necessary, from time to time, to go to war in the service of one's liege lord, this included the disagreeable prospect of death or dysentery, sleeping on the cold, stony ground or baking in one's chain mail under a blazing sun. There was excitement and renown to be won in war, but just as much renown could be won, at far less inconvenience, in the tournament of peace.

Tournaments were, at first, simply battles arranged on some pretext at a suitable rendezvous between parties of knights.  From these bloody conflicts there developed the tournament conducted according to a complex code of rules. In a tournament a knight could enjoy all the excitement, danger and glory of war, with none of the dirt, flies, disease or discomfort. After the fight he could soak his bruised, bloody limbs in a warm bath, eat a good dinner and retire, appropriately accompanied, to a soft bed. In war he might win fame and fortune; in tournaments he could win these and much more. Fundamental to the tournament was the idea of chivalrous and romantic conduct. A knight selected a lady; beautiful and preferably married to a husband of slightly higher rank. In her honor he would fight. If he fought successfully, he expected to receive his reward. It was considered downright disgraceful - absolute treachery - for a lady to refuse her favors to a knight who had fought in her honor. From these bloody conflicts there developed the tournament conducted according to a complex code of rules. In a tournament a knight could enjoy all the excitement, danger and glory of war, with none of the dirt, flies, disease or discomfort. After the fight he could soak his bruised, bloody limbs in a warm bath, eat a good dinner and retire, appropriately accompanied, to a soft bed. In war he might win fame and fortune; in tournaments he could win these and much more. Fundamental to the tournament was the idea of chivalrous and romantic conduct. A knight selected a lady; beautiful and preferably married to a husband of slightly higher rank. In her honor he would fight. If he fought successfully, he expected to receive his reward. It was considered downright disgraceful - absolute treachery - for a lady to refuse her favors to a knight who had fought in her honor.

Obviously, there was a direct conflict between the Christian ideal of monogamy and what can only be described as polite aristocratic adultery, which quickly brought the wrath of the Church upon all who participated. The French excelled in this department, whereas in England, a tournament was regarded more as serious training for war. English contests became so savage that the Church of England eventually forbade the Christian burial of those killed in tournaments. "Those who fall in tourneys will go to hell", scolded one monk. Tournaments were generally viewed with disapproval by the Church because they distracted the knights from the crusades, and by the state because of the unwarranted loss of life. Popes preached against them and Kings regarded them with unease, nervous about the potential threat a large gathering of military forces could impose on their politically unstable regions. Both were quite powerless to stop them. The knights' enthusiasm was already too great and the powers-to-be were forced to extend a grudging tolerance to the new sport.

The Statute of Arms for Tournaments, established in 1292, helped curtail the bloodshed at tournaments. Under this edict all Knights were automatically considered gentlemen, rather like the Congressional edict in the United States that makes all armed forces commissioned personnel "officers and gentlemen". They were required to abide by the ideas of chivalry and fair play, thus reducing the abhorrence of the church considerably.

At the end of the thirteenth century, when tournaments ceased to be miniature battles with no holds barred, they became organized spectacles, subject to accepted conventions and often fought with blunted weapons. To kill a man in a tournament was considered wrong - or, at the very least, unfortunate. For killing a horse there was no excuse. The knight's object became one of knocking off their horses as many opponents as possible, and in the process, breaking as many lances as possible; obviously the more lances a knight broke, the greater must have been the force of his charge and the higher his level of horsemanship.

There were three kinds of tournaments prior to the 17th Century:

MELEE' or TOURNEY PROPER - popular in the twelfth and thirteenth century. This form was the most brutal and costly in lives. All participants, upon hearing the charge, promptly  crashed onto the tournament field and proceeded to unhorse all others by any method at hand until a winner was determined. crashed onto the tournament field and proceeded to unhorse all others by any method at hand until a winner was determined.

INDIVIDUAL JOUST - an encounter with lances between two knights. The rules were simple. If a combatant struck either rider or horse he was disqualified. A clean hit to the center or "boss" of the shield shattering the lance, or unseating the opponent scored points. A low partition wall separating contestants was introduced in about 1420 strictly as a measure to reduce injury to horses.

PRACTICE TOURNAMENT - Involved very little ceremony and few rules. Practice targets were provided by either a quintain or rings. The quintain  was a wooden target mounted on a horizontal pole at which the knight aimed his lance. If the target was struck accurately, it would swing harmlessly aside; if struck off center, the weighted arm swung around with enough velocity to unseat the knight. The other form of jousting in the practice tournament was "riding at the rings", the surviving form of jousting with which we are most concerned. A ring was suspended on a cord, which was to be carried off on the tip of the knight's lance. Both the quintain and the ring joust were exercises that developed accuracy skills. These skills became increasingly important as individual jousts gained popularity. was a wooden target mounted on a horizontal pole at which the knight aimed his lance. If the target was struck accurately, it would swing harmlessly aside; if struck off center, the weighted arm swung around with enough velocity to unseat the knight. The other form of jousting in the practice tournament was "riding at the rings", the surviving form of jousting with which we are most concerned. A ring was suspended on a cord, which was to be carried off on the tip of the knight's lance. Both the quintain and the ring joust were exercises that developed accuracy skills. These skills became increasingly important as individual jousts gained popularity.

The huge melee' tournament which had dominated the twelfth and most of the thirteenth centuries began to lose popularity as the small-scale joust emerged towards the end of the thirteenth century. Jousting came to be a sport where the correct physical co-ordination of horse and rider resulted in a safe but spectacular splintering of lances. The manipulation of a powerful horse and a heavy lance, complicated by the restricted movement and vision imposed by armor, was a skill acquired only with patient practice at such devices as the quintain and the ring. century. Jousting came to be a sport where the correct physical co-ordination of horse and rider resulted in a safe but spectacular splintering of lances. The manipulation of a powerful horse and a heavy lance, complicated by the restricted movement and vision imposed by armor, was a skill acquired only with patient practice at such devices as the quintain and the ring.

Furthermore, it is probable that riding at the rings was perceived also as a display of chivalric romance. Winning knights were awarded customary "golden rings" along with kisses, in a formal and elaborate prize-giving ceremony by the ladies of the court, who had rapidly became central to the whole ideal of knighthood during the fourteenth  century. century.

The ring tournament has survived the longest. Accounts of famous festivals during the sixteenth and seventeenth century, including King's Day in honor of James I during the 1600s in England, list at least nine festival occasions where "running at the rings" was featured. Knowledge of these affairs was carried to the colonies by English cavaliers and officers in the mid-seventeenth century.

|

|